Sam Rizk, MD, FACS, recently performed his signature vertical deep plane facelift at the 59th Annual Baker Gordon Educational Symposium, demonstrating the advantages of vertical facelifts over traditional horizontal methods that often create a "pulled" appearance. He highlighted the use of tissue glue in his upward technique instead of traditional drains to prevent fluid buildup beneath the skin flaps.

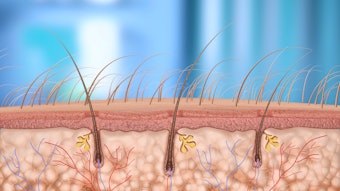

The deep-plane facelift targets the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS)—a layer of tissue and muscle underneath the skin, Rizk explains, unlike traditional facelifts that pull the skin or manipulate only the SMAS in a superficial way. The deep-plane facelift lifts the skin, SMAS and facial fat pads together as one unit.

“This technique releases key retaining ligaments, particularly near the cheek and jaw, which allows me to reposition drooping tissues more effectively,” Rizk says. “It’s especially effective for correcting sagging in the cheeks, nasolabial folds and jowls as well as improving jawline definition and neck laxity."

The vertical technique can be described as an upward lift, whereas traditional facelift techniques primarily pull the skin horizontally, making the mouth and eyes appear stretched.Courtesy of Sam Rizk

The vertical technique can be described as an upward lift, whereas traditional facelift techniques primarily pull the skin horizontally, making the mouth and eyes appear stretched.Courtesy of Sam Rizk

Horizontal lifts can result in aggressive scarring, especially as the use of drains can lead to malfunction and increase the risk of infection, leaks and significant scarring, Rizk adds. A vertical lift, however, prevents these unwanted results—addressing sagging skin, but also volume loss and tissue laxity.

The vertical deep-plane technique tucks the small incision scars into the tragus cartilage or positions them just inside the hairline at the temple so scarring is not visible post-op, Rizk says. After surgery, patients in recovery must adhere to strict care instructions and avoid any kind of sun exposure, he advises.

The recovery is smooth due to the use of tissue glue. Tissue glue, in comparison to using drains, helps seal the surgical site while minimizing the amount of fluid that can collect beneath the skin flaps. This tight seal promotes faster healing and keeps post-operative swelling and bruising to a minimum, making recovery more comfortable than conventional facelifts, Rizk says.

A recent study [1] found that vertical lifting for facial rejuvenation minimizes scarring and reduces surgery time. Suitable for patients prone to keloids or seeking less invasive options, vertical lifting provides notable aesthetic improvements with manageable complications.

The best candidate for a vertical deep plane facelift is someone who is experiencing sagging in the cheeks, deep nasolabial folds, jowling around the jawline and a hollowness under the eyes.

Results last 10-15 years, designed to sustain a lifted look without continuous touch-ups, Rizk says. In fact, frustration around consistent touch-ups is what drives patients to purse this specific face lift–a preventive procedure for many, he adds.

“In the last 5 years alone, the average age [for facelifts] has changed from 50 to 40, and most of it comes down to filler fatigue—they’ve simply had enough of repeated cosmetic tweaks,” Rizk says. “Patients want to look their best now instead of later, and they don’t want an upkeep.”

References:

1-https://journals.lww.com/prsgo/fulltext/2025/01000/transtemporal_endoscopic_deep_plane_face_lift.53.aspx